In the spring and summer of 2017, we spoke to the innovation leads of over 20 utilities. There’s good reason that utilities aren’t well known for innovation, but there’s still much to learn about how they do innovation.

What We Did:

- Spoke to the innovation leads at 21 utilities. Sometimes innovation leads were in R&D, some in strategy or strategic planning, others still in business development

- Asked them a standard list of questions related to innovation. This list is a bit too long to list here in entirety, but topics included:

- Strategy – What do you hope to achieve with innovation and why?

- Structure & Process – How do you manage, measure, and govern innovation?

- Execution – How do you prioritize and structure your innovation activities?

What We Learned:

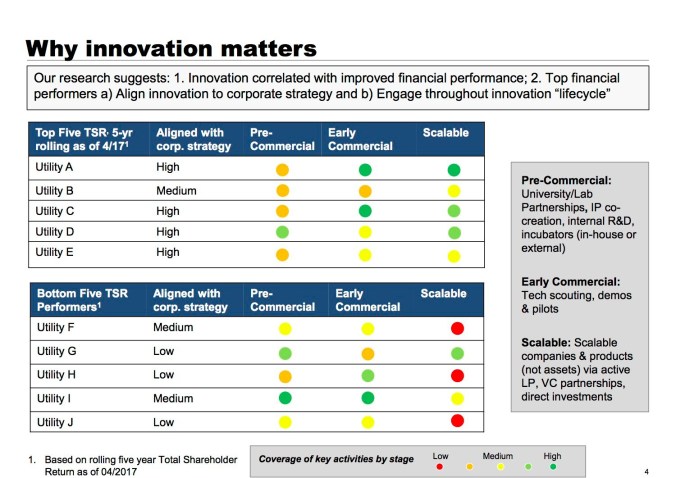

- Innovation correlated with improved shareholder performance

Those utilities we interviewed who aligned their innovation strategy, dollars and activities in a way that helped them execute their corporate strategy, had superior shareholder performance.

- Top performers focus. In other words, they DON’T do everything equally well. While they tend to have “bets” across the innovation spectrum (from early R&D stuff through to more mature investments) they focused on certain stages or areas unequally. In other words, specific areas or activities that were aligned to corporate strategy drew an outsized portion of time, attention, and dollars.

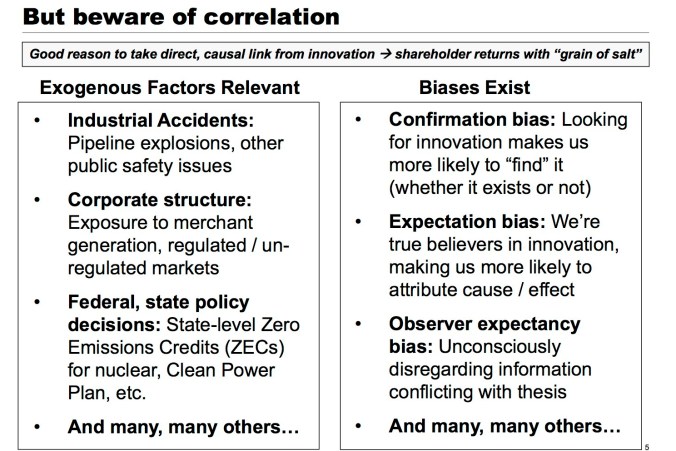

- Correlation does not imply causation:

Don’t forget that famous dictum. There’s all sorts of good reasons to avoid drawing a direct, casual link from innovation to improved financial performance. All sorts of exogenous factors affect financial performance – from pipelines unexpectedly exploding, to other accidents or natural disasters that have nothing to do with innovation – so take the correlation with a big “grain of salt”

- But innovation capability helps strategy execution: Whether or not you can draw a direct line from financial performance to a utility’s ability to innovate, our work indicates that utilities better able to innovate – and tie innovation activities to execution of a corporate strategy – are in a better position, financially or otherwise.

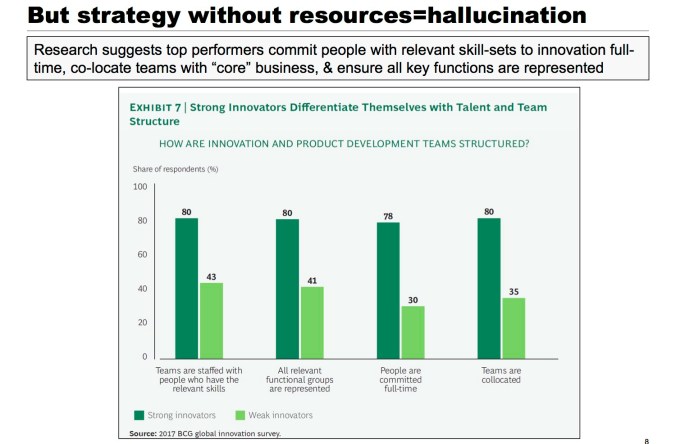

- Dedicate people full-time, in the same place, ensure they have the right skills and represent the right functions:

All credit to the consulting firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG) for this finding. They looked at top innovators across industries and found that teams are staffed with people who have skills relevant to innovation-related positions, that all relevant functional groups are represented in innovation teams, that these teams are located with the “core” business, and that they are staffed full time